A vineyard is flooded along 4th Avenue in Corcoran, Calif. (Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

BY JESSICA GARRISON, SUSANNE RUST, IAN JAMES, LA Times

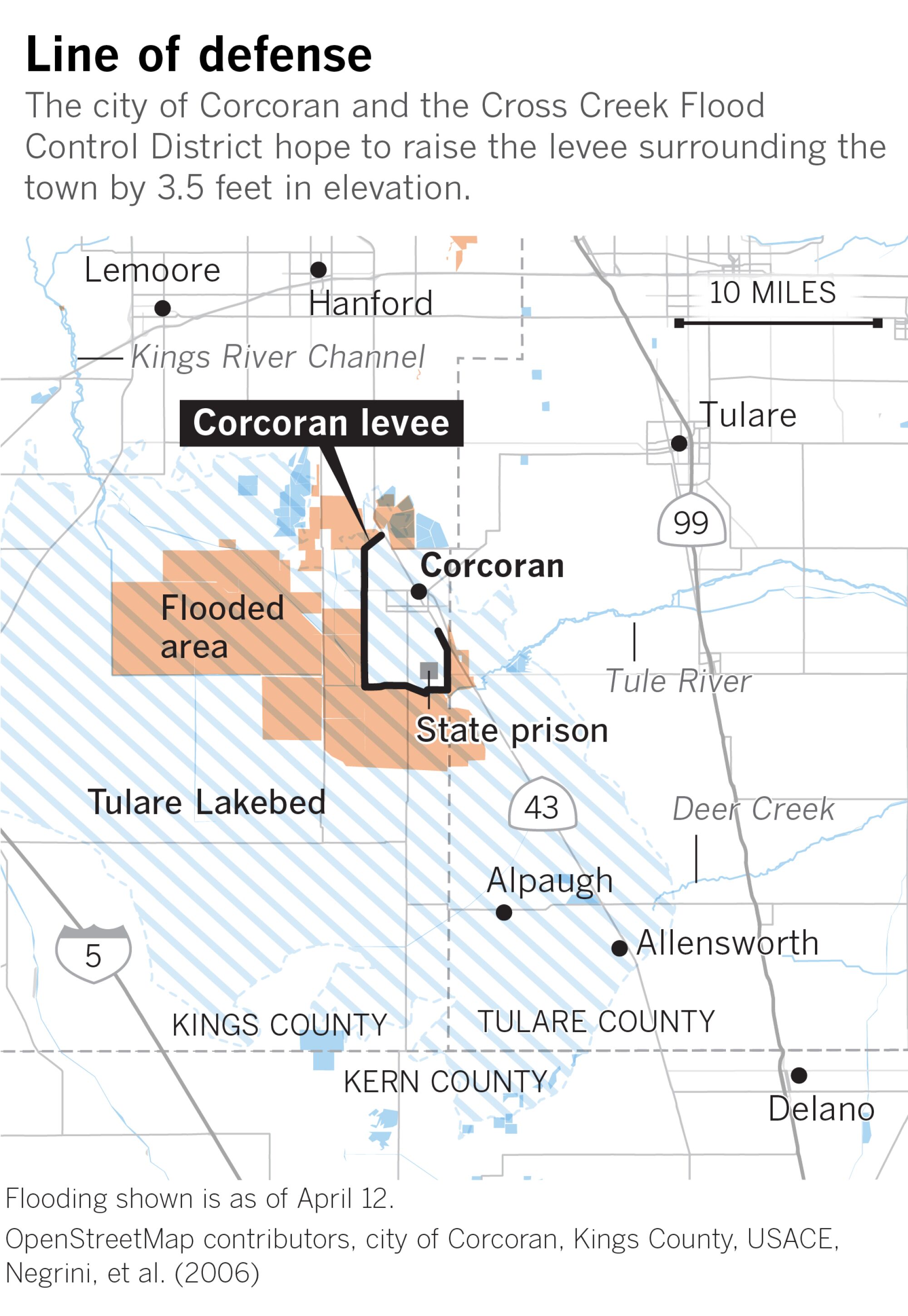

CORCORAN, Calif. — Just west of this normally dusty prison town, a civic nightmare is unfolding: Tulare Lake, a body of water that did not exist just two months ago, now stretches to the horizon — a vast, murky sea in which the tops of telephone poles can be seen stretching eerily into the distance.

Anxious residents in this Central Valley city of 22,000 know all too well that the only thing keeping this growing lake from inundating their homes and businesses — as well as one of the state’s largest and most crowded prison complexes — is a 14.5-mile-long dirt levee that rises up from sodden earth to the west, south and east.

And that levee, according to city officials and local farmers, could be in big trouble.

They worry that this nondescript earthwork may be too low to hold back the millions of gallons of melted snow that are expected to course into the Tulare Lake Basin as summer sunshine warms the slopes of the Sierra Nevada. They worry even more that with water sloshing against the levee for up to two years, it may start to erode and breach.

Many here say they are perplexed and frightened that state and federal officials don’t seem to be taking the threat seriously since the federal government has estimated that flooding would cause $6 billion worth of damage. They note that both California State Prison, Corcoran, and the California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility — a dual prison complex that holds about 8,000 incarcerated men and employs many local residents — stand in the path of potential destruction.

“Nobody has ever seen that much snow,” said Jason Mustain, a clerk at the Corcoran hardware store and a former firefighter. “Of course, I’m stressed.”

Related news:

San Joaquin Valley farmers dig in for the next battle: an epic Sierra snowmelt

Five things you should know about California’s drought

A bottle of Tums antacid tablets rattled in the cup holder of Kirk Gilkey’s truck recently as he drove around the area surveying the rising water.

Gilkey’s family has been farming in the area for generations. He said this is the first year in decades that his farm won’t plant cotton because of flooding. But what distresses him most is not the financial pain big farmers will experience but the hardship that will be visited upon workers and their families who are dependent upon agriculture for their livelihoods.

“People are scared,” he said. If “Corcoran floods, it’ll be a ghost town after. It won’t survive.”

If you liked this post you’ll love our daily environmental newsletter, EnviroPolitics. It’s packed with the latest news, commentary, and legislative updates from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, New York, Delaware…and beyond. Don’t take our word for it, try it free for an entire month. No obligation.